Debating Truth, Knowledge, Accountability

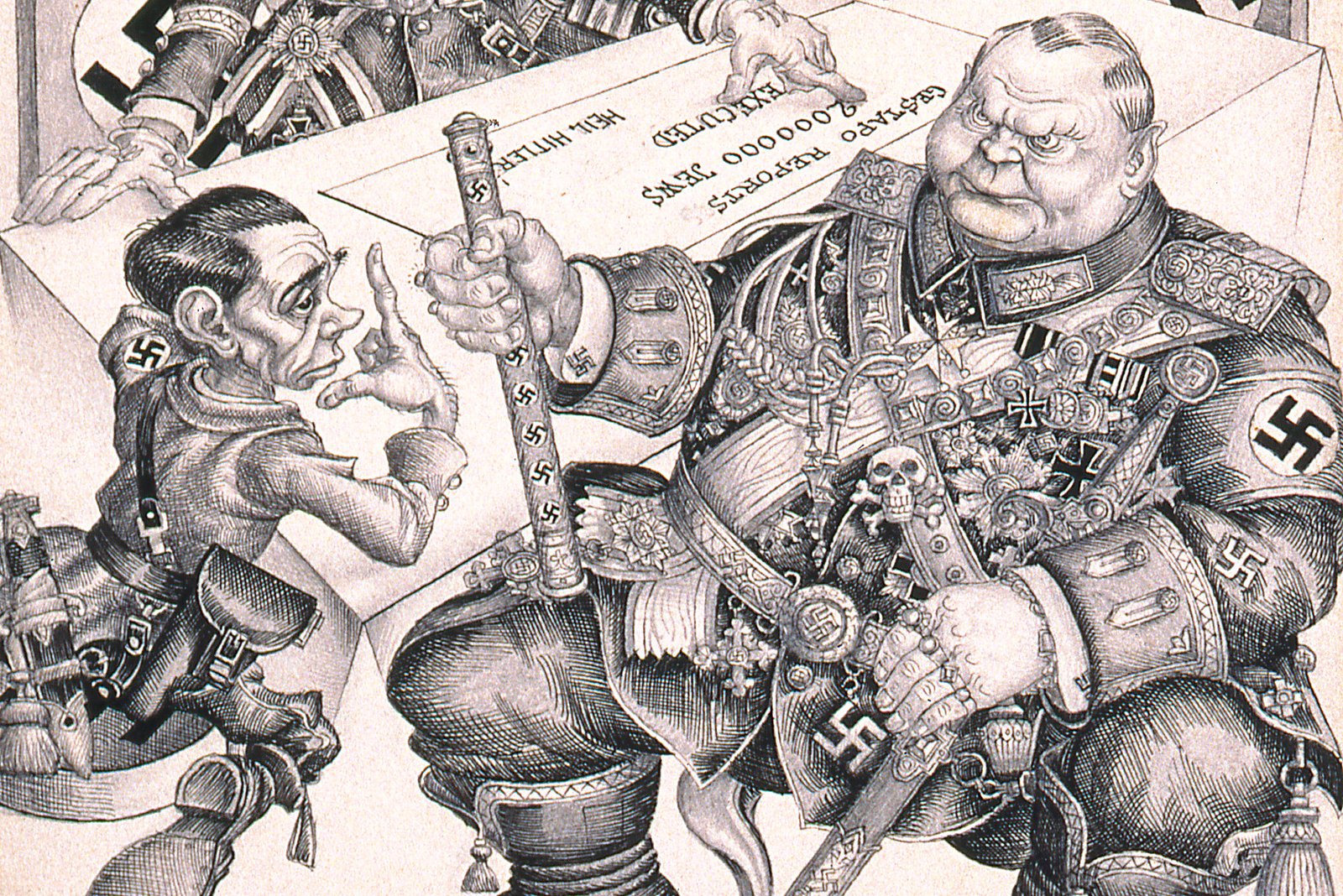

The 2025 film Nuremberg focuses on insight Dr. Douglas M. Kelley acquires serving as prison psychiatrist for the high-ranking Nazi leaders standing trial in Nuremberg from November 1945 to October 1946. Below is an exchange between Kelley and Hermann Göring, the highest ranking Nazi prisoner who, at one time, had been second in command to Hitler. It is the beginning of March 1946. They are discussing in Göring’s cell the somewhat surprising news that Göring will be put on the witness stand. Most lamentably, this highly revealing interview was not included in the script, hence Russell Crowe playing Göring and Rami Malek playing Kelley were deprived of a rare opportunity to showcase their considerable talents. But such is Hollywood. Always a heartbreaker.1

Kelley: How will you defend yourself?

Göring: Have you any advice?

Kelley: How about telling the truth for once.

Göring: (laughs) You pretend to be fond of truth, but I don’t think so or you would believe what I tell you. You choose the truth you prefer, like any victor. What I say makes no difference.

Kelley: We are asking you to testify to learn the truth.

Göring: You do not fool anyone. As victor, you will exhibit me to the world at your so-called trial as your prisoner to prove my guilt, of which you are convinced already.

Kelley: We are committed to the truth — to learning how . . . how . . . all this happened.

Göring: How can you learn this? You ask me questions. I tell you the truth. You reject it, as your court will. You don’t want the truth. You don’t accept the truth.

Kelley: We are committed to truth, and justice.

Göring: I laugh at your justice. I laugh at your truth. As victor you will make your prisoner testify, and I will testify, and I will tell the truth, and you will use your power to cut me down. I shall defy you nonetheless. You will see. But keep always in mind: No nation can judge another nation.

Kelley: We are a tribunal of four nations.

Göring: (laughs) Our four enemies. A conspiracy. One of your charges against us, I think. You won the war, that’s all. It does not make you morally superior. You have no authority to judge me.

Kelley: Might doesn’t make right?

Göring: No.

Kelley: You say that now. Having lost.

Göring: My perspective is not changed.

Kelley: So you won’t be claiming moral superiority in your defense.

Göring: I have to contradict you. The victor may be right. I say only victory proves who is more powerful. Moral superiority lies with those who obey existential imperative. That is my claim and my defense, which you reject. Like all victors, you have power to dictate truth, and you intend to.

Kelley: You don’t approve of dictating truth?

Göring: (laughs) On the contrary. It is most useful. Your embarrassment is you do not and are up to the ears in it with your show trial.

“I am your prisoner. You may ask what you like. It will pass the time.”

Kelley: Let me ask you something about that — dictating truth — if you don’t mind. Something I’m curious about.

Göring: I am your prisoner. You may ask what you like. It will pass the time.

Kelley: You’re on trial for causing millions of deaths.

Göring: Casualties of war. I think you had some.

Kelley: I’m thinking of the children, the disabled children, the German children you transported to gas installations. The feeble-minded and elderly you drove in vans fitted up to gas them on the way to the crematorium where you delivered their bodies. Not casualties of war, Herr Göring. There was no war. It was your domestic policy. To round up and kill people you called useless mouths, lives unworthy of life, the genetically inferior.

Göring: I know nothing of it.

Kelley: Seventy thousand people killed within a year and a half and you, second in command, knew nothing?

Goring: Rumors. I pay no attention to them.

Kelley: So you heard these rumors?

Göring: No. I hear them now from you.

Kelley: You kept books: names, dates, ages, locations, and — I’m curious about this, Herr Göring — a false cause of death. Why bother?

Göring: Why false? Clearly, more of your rumors. We keep accurate records.

Kelley: You created and preserved records that very literally dictated truth. You couldn’t say you gassed them.

Göring: Who says we did? The victor again tells me what truth is. I have no choice but to submit to this abuse because I am the prisoner.

“Rumor has it your Reich required space.”

Kelley: Maybe I can ask you about something you did know about.

Göring: That would be more useful.

Kelley: Rumor has it your Reich required space.

Göring: Everyone requires space.

Kelley: Yes, everyone does. That’s the point.

Göring: Is it a question? I cannot answer.

Kelley: You required someone else’s space who required that space.

Göring: Do you make a joke for me?

Kelley: No. To get that space, you invaded peaceful countries — there was no war — weeded out those you considered genetically inferior, just as you did with your disabled at home, marched them out of town, lined them up along pits dug in fields to hold their bodies, and shot them. Over a million civilians were done to death this way. I say again: as second man in Germany, you must have known about this.

Göring: I am sorry to disappoint you.

Kelley: Surely you knew of Himmler’s directive in June 1941 to exterminate 30 million Slavs. You heard about it from the witness Von dem Bach-Zelewski in court. In January. Do you remember that?

Göring: Yes. First of all, it was not an order but a speech. Secondly, it was an assertion by Zelewski. And thirdly, in all speeches that Himmler made to subordinate leaders, he insisted on the strictest secrecy. In other words, this is a statement from a witness about what he had heard and not an order. Consequently, I have no knowledge of this nonsense.

Kelley: I did not say it was an order. I said it was a directive. From Himmler.

Göring: I emphasize that I know of no such directive.

Kelley: You did not know about it. Very well. Tell me, in the German totalitarian state was there not a governing center, Hitler and his immediate entourage, for which you acted as deputy? Could Himmler of his own volition have issued a directive for the extermination of 30 million Slavs without authority from Hitler or you?

Göring: Himmler gave no order to exterminate 30 million Slavs. The witness said he made a speech. To issue such an order, Himmler would have to ask the Fuehrer, not me, who would have told him immediately that such a thing is impossible.

Kelley: Just impossible? No other reason for not issuing such an order? Then let me ask you this: Is it not true that the directives and the orders of the OKW2 with regard to the treatment of the civilian population in the occupied Soviet territories were part of the general directives for the extermination of the Slavs?

Göring: Not at all. At no time has there been a directive from the Fuehrer, or anybody I know of, concerning this rumor about the extermination of Slavs.

Kelley: What about the rumor that your Reich required grain? Heading into the third year of war, rumor has it Germany had run out.

Göring: Everyone needs grain. This is true.

Kelley: Were you not, as delegate for the four-year plan, in full charge of planning the economic exploitation of all the occupied territories as well as realizing those plans?

Göring: I assumed responsibility for the economic policy in the occupied territories and gave the directions for the exploitation of those territories. That is correct.

Kelley: Can you tell me how many million tons of grain and other products were exported from the Soviet Union to Germany during the war?

Göring: No. But I am sure it is by no means as large as you state.

Kelley: Wasn’t your quota to seize and export 90% of Soviet grain, knowing it meant the death by starvation of millions of Slavic people? And isn’t it true that Himmler’s so-called extermination instructions were issued one month after your four-year plan was finalized and that both were perfectly consistent with your Reich’s overall mandate of ridding the occupied territories of genetic chaff, just as you rid yourself of your disabled at home? Rather than knowing nothing of Himmler’s directive to exterminate millions of Slavs, as you say, you welcomed it as advancing your objectives.

Göring: You are mistaken. As far as taking grain or anything else from occupied territories, I decreed our soldiers to take all they could buy.

Kelley: I say to you again, Herr Göring, Himmler’s mass extermination of Soviet citizens carried out by the Einsatz Kommandos was the logical complement of your plan to starve millions of Soviet citizens by expropriating their grain for German use. I say as well that, though you may not have issued the orders, you were aware of those actions and the intent.

Göring: I was not. Einsatz Kommandos were an internal organ of Himmler which he kept very secret. I do not know what their orders were or how they carried them out. But I can say and do say that we did all that was necessary to defend our culture, our way of life, our future, our race, our Reich.

Kelley: From what? There was no threat. There was no enemy.

Göring: As you keep saying. And keep judging. Why should I listen?

Kelley: Something you never did. Judge, that is. You selected, you condemned, you killed. Your systems of extermination were in full operation. We, on the other hand, as victors no less, are holding trials to determine the guilt of those who did that. We are required to provide evidence of what happened and why, determine who was responsible if anyone, whether those acts were criminal, and if its perpetrators should be punished.

Göring: Put to death.

Kelley: If the court finds that appropriate. But we are asking you to testify. You will be testifying —

Göring: To your court and your judges who serve your values and your moral perspective staged here within the ruins of Nürnberg within the walls of this prison within your justice system. Is there any doubt how they will judge?

Kelley: Outside these walls, according to your justice, you would have had my skull crushed without a second thought.

Göring: Within these walls you intend to crush mine.

Kelley: You see no difference?

Göring: No. What you are subjecting me to now demonstrates your point.

Kelley: What you are being subjected to, Herr Göring, is a trial in a court of international justice, not a Genickschuss.

Long silence as Göring stares at Kelley. Kelley returns his look.

Göring: Sie können gerne mit mir Deutsch sprechen, Herr Doktor Kelley, wenn es Ihnen lieber ist.

Kelley: I don’t speak German.

Göring: (laughs, pulls two decks from sack near table) Perhaps we should take a break. Double solitaire?

Kelley: You’re on.

They play amiably but awkwardly using Göring’s cot as a table.

Kelley: As second man in Germany, you were certainly aware of OKW’s order giving officers permission to shoot Soviet civilians without trial.

Göring: Why do you say so?

Kelley: Such an order must have been distributed to you.

Göring: I apologize if I contradict you. The higher the office, the less I would be concerned with a departmental matter. Orders about handling civilians would go to the department responsible to carry them out. If my rank were much lower, then I might have had more knowledge of such an order. As Reich Marshal of the Greater German Reich, only direct orders from the Fuehrer and signed by the Fuehrer were sent to me.

Kelley: But you knew about this order?

Göring: I only have heard about it here. I want to also emphasize this concerns an order from the Fuehrer, which could not be questioned by the troops. My involvement was not necessary.

Kelley: You just said orders sent directly from the Fuehrer would go to you.

Göring: A direct order from the Fuehrer and signed by the Fuehrer, yes. An order not signed by the Fuehrer but beginning with the words “By order of the Fuehrer” or “On the instructions of the Fuehrer” would go to the department concerned. I understand this order went to Air Force Operations Staff and General Staff. If those departments had accorded it enough importance to require my personal attention, they would have reported it to me verbally.

Kelley: And it was important enough to report to you, was it not?

Göring: No. This was not the case. I did not hear of it.

Kelley: But this order should have been reported to you.

Göring: If every order which did not require my intervention would have been reported to me, I should have been drowned in a sea of papers. That is why only the most important matters were reported to me.

Kelley: You say only the most important matters were reported to you?

Göring: That is correct.

Kelley: An order issued by Hitler that instructed troops to violate the Geneva Convention by shooting Soviet civilians without trial was not important enough to be reported to you?

Göring: That order of the Fuehrer was so clear that a subordinate commander, even a commander-in-chief, could not alter it.

Kelley: Now you’re saying there was no need for you to see any order coming from Hitler because you had no authority to alter it.

Göring: That is correct.

Kelley: So you had no knowledge of this order either.

Göring: No.

“Himmler kept these matters very secret. I did not know of details of concentration camps.”

Kelley: And I guess you, the second man in the Reich, knew nothing of the concentrations camps?

Göring: I did not know anything about what took place there or the operations used after I was no longer in charge. That was 1934.

Kelley: Deputy Group Leader Höttl of the Foreign Section of the Security Section of Amt IV of the RSHA3 says approximately four million Jews were killed in the concentration camps. Certainly with your power in the Reich, you were aware of that?

Göring: No. I already mentioned Himmler kept these matters very secret. I did not know of details of concentration camps.

Kelley: I am not talking about details. I am talking about the murder of four million people. Are you suggesting nobody in power in Germany except Himmler knew about that?

Göring: I did not know of this figure. It is another of your rumors, I think.

Kelley: You’ve told me, Herr Göring, that your Reich had the highest necessity to plunder countries for their space, their resources, even the population for its labor.

Göring: If we conquer, we have a right to plunder. Soldiers who have done so much cannot be left to gain the least.

Kelley: Let’s take a closer look at what your Reich was stealing. It wasn’t just space, grain, or labor. Your Reich stripped gold from teeth, wedding rings from fingers, eye-glasses from faces, hair from heads, in some cases, skin from bodies. Your higher Nazi purpose, Herr Göring, had members of your Reich ransacking the corpses of your victims.

Göring: I do not know of it. More of your rumors.

Kelley: Think for a minute, Herr Göring, about what you are calling rumors. You are a very smart man. We all know it. Does it not occur to you that these monstrous acts — what you like to call rumors — are no aberration? Whether you knew and approved or did not, each horrific crime was consistent in spirit, word, and deed with the ideology of the Reich of which you were fully informed and fully approved and that those acts were in fact the logical extension of edicts you yourself put in place to eliminate your genetic chaff starting in 1933 and culminating in your July 1941 order to Himmler to prepare what you prefer to call, not a final, but total solution of what you also called the Jewish problem. There is no contradiction between what you started and what others attempted, however gruesome, to finish. You must take full responsibility, whether you received the order or not.

Göring: A victor makes himself judge. It is what any child would do.

Kelley: I submit to you, Herr Göring, that you invaded nations, plundered the wealth of populations, murdered your millions of victims not out of strength, but weakness. Your rampage exposed your Reich — I hesitate to even say this to you — as a parasite, a greedy, virulent parasite. One must wonder what you would have done when you ran out of victims. But now you’re caught and find yourself hard-pressed to frame rampant mass murder as existential imperative to escape a hangman’s noose. Isn’t that your truth that you say I reject? Can you deny it?

Göring: As judge in these so-called trials, all you will demonstrate to the world, day after day, witness after witness, is that a victor’s justice is meaningless. The victor judges to justify his own crimes.

Kelley: If you had been victor?

Göring: We would have had a place for you.

Kelley: I don’t think I would have fit in.

Göring: (laughs) Like a hand in a glove.

Guard: (bangs on door) Lunch!

Kelley: I object to that statement.

Göring: (laughs) You are the victor. You may object to everything. If you permit me to be excused, my time to dine has arrived.

Kelley gestures for Göring to proceed.

Kelley: I hope I didn’t offend with my frank statements.

Göring: On the contrary, you are good practice for me. I think I will get worse very soon.

Göring exits. Kelley follows.

- Major sources:

Nuremberg Trial Proceedings Vol. 9, transcripts from Day 80 (Wednesday, March 13, 1946) through Day 88 (Friday, March 22, 1946), The Avalon Project, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/subject_menus/imt.asp

22 Cells in Nuremberg by Douglas M. Kelley, MD.

Nuremberg Diary by Gustave M. Gilbert. ↩︎ - Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (Armed Forces High Command) was the supreme military command and control staff of Nazi Germany during World War II and directly subordinated to Adolf Hitler. ↩︎

- Reich Security Main Office (German: Reichssicherheitshauptamt). ↩︎